Sharing is caring!

I am currently researching the literature on Pseudomonas aeruginosa for my next paper. Therefore, I thought I'd compile some facts about P. aeruginosa and list ways of controlling this 'superbug' in water systems.

As I'm sure people involved in infection control in hospitals know well, P. aeruginosa is present in hospitals environment. It is dangerous to health because it can lead to various types of infections including pneumonia.

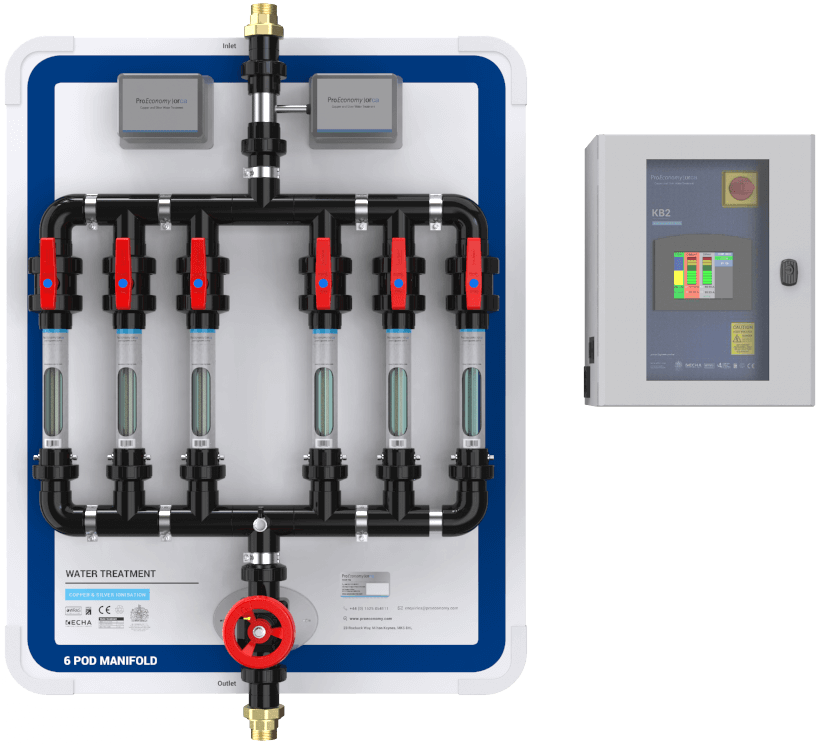

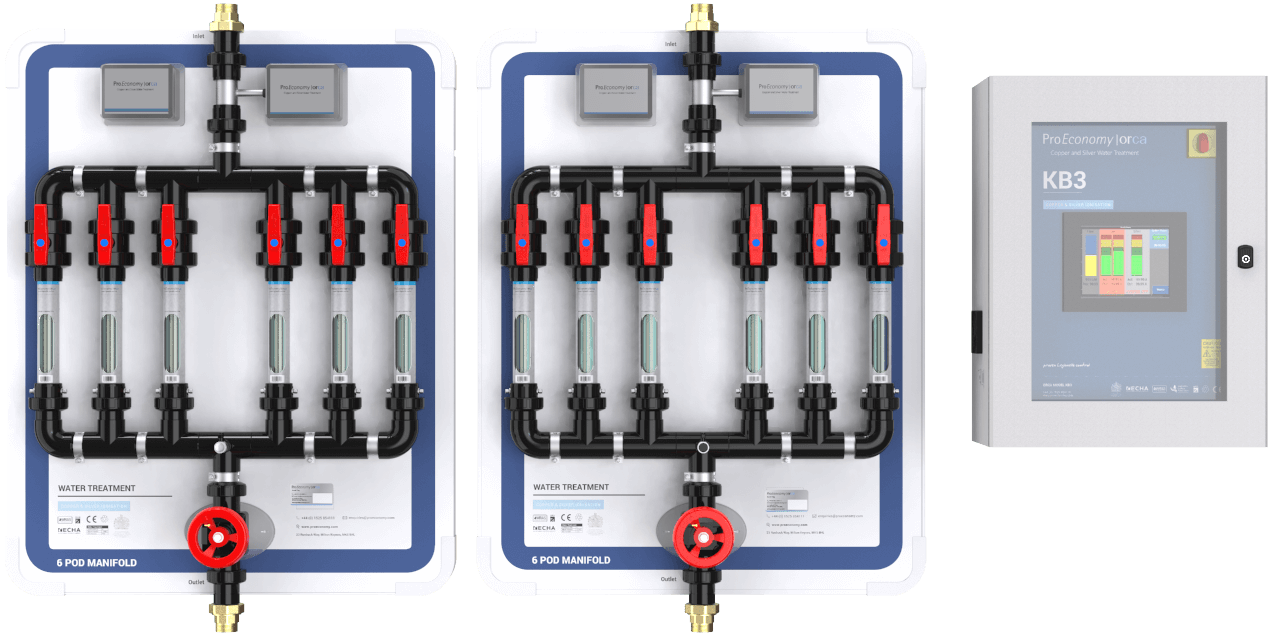

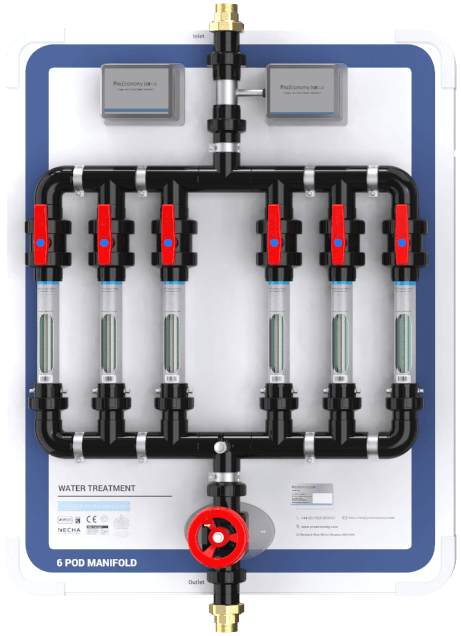

It is particularly important when it affects immunocompromised patients in hospitals’ intensive care units (Oliver et al 2015). You can find out more about pseudomonas control and management with ProEconomy's Orca system here.

10 Facts About Pseudomonas Aeruginosa

1. P. aeruginosa can be transmitted by direct contact with water through: drinking, bathing, contact with wounds, splashing from water outlets (taps), inhalation of water droplets (aerosols), and equipment rinsed in contaminated water (DH Estates and Facilities Division 2016).

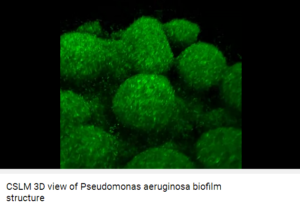

2. P. aeruginosa is usually present in biofilms formed in pipes, taps, shower heads, and dead-end pipes. Its presence is particularly evident within the last two metres before the point of discharge and devices fitted to the tap outlet, such as mixing valves, solenoids or outlet fittings, may exacerbate the problem by providing ideal conditions and nutrients for microbial growth (DH Estates and Facilities Division 2016).

3. P. aeruginosa grows best at 37 ℃ but it is tolerant to a wide range of temperature, being able to multiply at temperatures as low as 4 ℃ and as high as 42 ℃ (Lutz and Lee 2011).

4. In biofilms, some P. aeruginosa cells can withstand temperatures of 85℃ (Kisko and Szabo-Szab, 2011).

5. P. aeruginosa is more likely to infect those who are already very ill, including patients in critical care units, such as high dependency, transplant, burns, and renal units (Oliver et al 2015).

6. P. aeruginosa is believed to be responsible for approximately 10% of hospital acquired infections (Mena and Gerba, 2009).

7. P. aeruginosa causes the following types of infections: blood infection (septicaemia), heart infection (endocarditis), bone infection (osteomyelitis), nervous system infection (meningitis), urinary tract infection, gastrointestinal disorders, wound infections, respiratory tract infections and pneumonia (Mena and Gerba, 2009). In fact, P. aeruginosa is the number one pathogen causing ventilator associated pneumonia and burn wound infections, both associated with a very high (>30%) mortality rate (Vincent 2003).

8. P. aeruginosa already has a high natural resistance to many antibiotics and it also can develop resistance to new antibiotics by a variety of means. A few isolates of P. aeruginosa are resistant to all reliable antibiotics and this problem seems likely to continue to grow (Livermore 2002).

9. When it comes to resistance to antibiotics what makes P. aeruginosa unique is a combination of the following: the species' inherent resistance to many classes of drugs; its ability to mutate to acquire resistance; and its high and increasing rate of resistance locally (Livermore 2002). It is no wonder it is called a 'superbug'.

10. Latest research published in Respiratory Medicine found that an electronic nose device could accurately identify volatile organic compounds-VOC breath-prints of clinically stable bronchiectasis patients with airway bacterial colonisation, especially in those with P. aeruginosa (Suarez-Cuartin et al 2018).

The Importance Of Facts About Pseudomonas Aeruginosa

An important message I've got from these facts about P. aeruginosa is that it poses a growing threat because of its astonishing capacity for developing resistance to nearly all available antibiotics. This is due to the selection of mutations in its chromosomal genes and from its increasing ability to transfer resistance (Oliver et al 2015). I think that because of P. aeruginosa's incredible ability to dodge antibiotics, it has become ever more important to control P. aeruginosa in hospitals' environments, including water, to avoid infection of patients.

In April 2017, the UK government extended the surveillance of bacteraemias (blood infection by bacteria) caused by Gram-negative organisms to include P. aeruginosa which shows how serious infection by this microorganism has become. The intention is to reduce Gram-negative bacterial infections by 50% by 2021. Read Ruth May’s letter under ‘Ambition to halve healthcare associated Gram-negative bloodstream infections’ section of the March 2017 edition of the Provider Bulletin by following this link.

10 steps to reduce contamination by P. aeruginosa in hospitals

1. Clean taps before cleaning the rest of the wash-hand-basin. During cleaning there is a risk of contaminating tap outlets with microorganisms from the bowl if the same cloth is used to clean the bowl of the hand basin and then the taps.

2. Do not dispose of body fluids at the wash-hand-basin but use the dirty utility area instead.

3. Do not wash any patient equipment in wash-hand basins.

4. Do not use wash-hand basin for storing used equipment awaiting decontamination.

5. Do not dispose of used environmental cleaning fluids at the wash-hand basin.

6. Make sure to use water from outlets shown to be safe by risk assessments when washing vulnerable patients such as neonates.

7. Keep the water flowing. Regularly flush all taps that are used infrequently on augmented care units, at least daily in the morning for 1 minute (DH Estates and Facilities Division, 2016).

8. Replace thermostatic mixing valves with conventional taps. There is some evidence that the more complex the design of the tap assembly, for example sensor taps, the more prone to Pseudomonas colonisation the outlet may be (DH, 2012).

9. Clean and descale outlets (taps and shower heads) regularly.

10. Implement and maintain an effective Pseudomonas control measure.

A study by Huang et al (2008) showed that copper ion concentrations of 0.1–0.8 mg/L and silver ions concentration of 0.08 mg/L achieved more than 99.9% reduction of P. aeruginosa after 6 hours. The copper and silver ionisation Orca system from ProEconomy Ltd has been successful at controlling P. aeruginosa in water systems of over 200 sites, including many hospitals in the UK, for almost 25 years.

References

DH Estates and Facilities Division (2016). Health Technical Memorandum 04-01: Safe water in healthcare premises, Part B: Operational management. DLondon, UK. [Online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/524882/DH_HTM_0401_PART_B_acc.pdf [Accessed Feb 2018].

DH (2012). Report on the review of evidence regarding the contamination of wash-hand basin water taps within augmented care units with Pseudomonads. 43 pp. DH.

Huang H-I, Shih H-Y, Lee C-M, Yang TC, Lay J-J, Lin YE (2008). In vitro efficacy of copper and silver ions in eradicating Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Acinetobacter baumannii: Implications for onsite disinfection for hospital infection control. Water Research 42(1-2):73–80.

Kisko G, Szabo-Szabo O (2011). Biofilm removal of Pseudomonas strains using hot water sanitation. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Alimentaria 4:69-79.

Livermore DA (2002) Multiple Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Our Worst Nightmare? Clinical Infectious Diseases 34:634-64.

Lutz JK, Lee J (2011). Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in swimming pools and hot tubs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8:554-564.

Mena KD, Gerba CP (2009) Risk Assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Water. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 201:71-115.

Oliver A, Mulet X, Lopez-Causape C, Juan C (2015). The increasing threat of Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-risk clones. Drug Resistance Updates 21-22(Jul-Aug 2015):41-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2015.08.002

Suarez-Cuartin G, Giner J, Merino JL, Rodrigro-Trovano A, et al (2018). Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and airway bacterial colonization by an electronic nose in bronchiectasis. Respiratory Medicine (In Press).

Vincent JL (2003). Nosocomial infections in adult intensive-care units. Lancet 361(9374):2068-2077. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13644-6