This article intended to give readers some knowledge about Legionella and Legionnaires’ disease, and existing Legionella control methods and prevention measures, especially in hospitals and nursing homes. I wrote this article from notes I made while doing my background reading on Legionella during my internship with ProEconomy Ltd.

This article intended to give readers some knowledge about Legionella and Legionnaires’ disease, and existing Legionella control methods and prevention measures, especially in hospitals and nursing homes. I wrote this article from notes I made while doing my background reading on Legionella during my internship with ProEconomy Ltd.

News and scientific publications have been tracking the outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease for a long period of time.

The latest nursing home outbreak, in Forsyth County, NC, USA, included six cases, while 180 cases have been identified in Canada in 2012.

Community outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease have occurred in various boroughs in New York city since 2006.

Initially, an outbreak in the Bronx resulted in 29 cases including one death, while around 10 cases were registered in Manhattan and Queens in 2008, luckily with no deaths.

After a period of time, cooling towers were identified as the source for the largest number of cases (138) in the Bronx outbreak with suspected 16 deaths in 2015. However, only residential potable water could be tested before this time (Lapierre et al. 2017, Weiss et al. 2017).

What is Legionella?

Legionella is the primary cause of Legionnaires’ diseases, a serious pneumonia illness which can kill those affected. L. pneumophila is the most common species of Legionella causing the disease. We associate the risk for water contamination with one main indicator, i.e. the amount of Legionella.

People over 50 years of age, especially men, new-born babies, immune-suppressed, and smokers are most at risk of contracting Legionella and developing Legionnaires’ disease. Basically, this is because these sections of the population have less lung capacity.

Surveillance and Disinfection

Surveillance and disinfection are two important ways of preventing Legionella contamination in drinking water, particularly in hospitals and nursing homes (Lin & Yu 2012). Monitoring Legionella’s environment is a necessary first step for prevention.

Although US Centres do not suggest routine environmental cultures for nursing homes and hospitals, the World Health Organisation and many other public health agencies in Europe encourage the surveillance for Legionella. This is because bedridden patients and immunosuppressed patients in some facilities could be better protected if surveillance could be achieved (Lin & Yu 2012).

Legionella Analyses Methods

The most common method to determine the numbers of Legionella in a water system is the plate count method. This gives results in colony forming units (CFU) per litre. However, cfu/L, as a designated parameter for the number of Legionella, does not tell the whole truth for predicting the risk of water contamination. New molecular biology PCR-based methods are more accurate. For example, qPCR (Collins et al. 2015) and MALDI-TOF (Trnková et al. 2018).

Legionella Control Methods

A previous blog post in this site has explained Legionella control methods, so, I will just briefly discuss their effectiveness.

Intermittent Disinfection

Lin & Yu (2012) reported on what was then a new approach called intermittent disinfection. This was introduced with intensive environmental monitoring of Legionella colonisation. They added that this innovative disinfection might be adopted due to its low cost and long-term effects of extending the recolonisation time for Legionella in water plumbing systems.

Systemic Disinfection

Lin et al. (2011) reviewed systemic disinfection methods (copper-silver ionisation, chlorine dioxide, monochloramine, ultraviolet light and hyperchlorination), a focal disinfection method (point-of-use filtration), and short-term disinfection methods (superheat and flush with and without hyperchlorination) in outbreak situations. Systemic means it treats the whole water system, while focal treats one specific point.

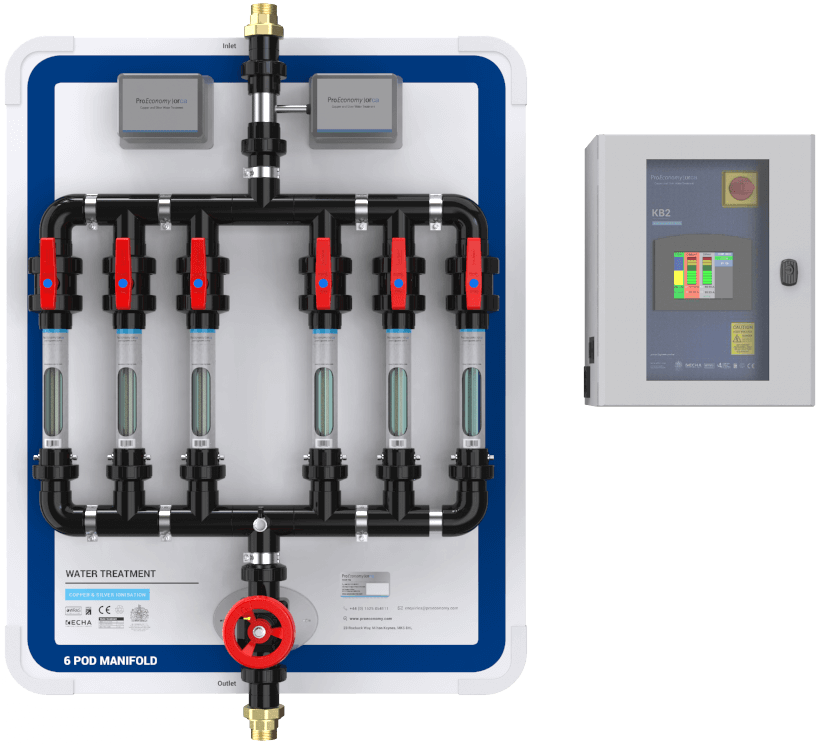

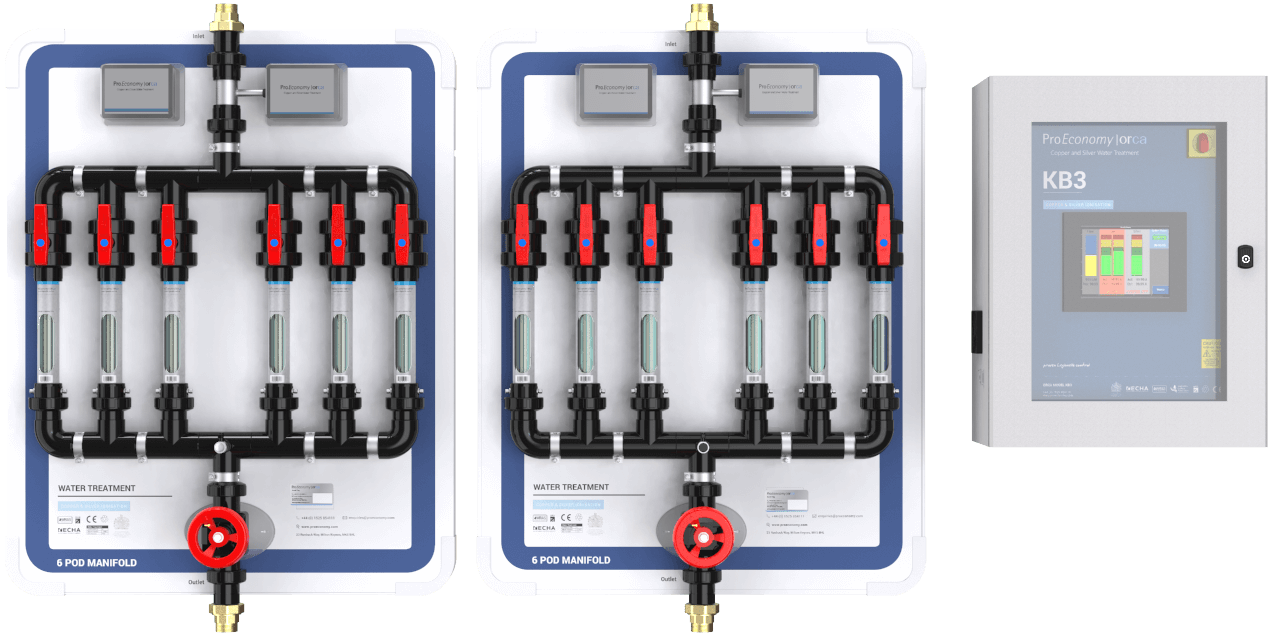

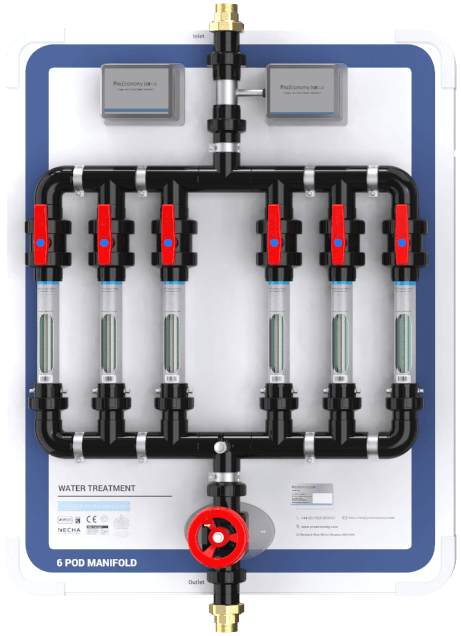

One systemic disinfection method, which many hospitals are using, is copper-silver ionisation (Lin et al. 2011, Stout & Yu 2003).

Copper-Silver Ionisation (CSI)

Copper-silver Ionisation (CSI) is currently one of the most useful systemic methods in controlling Legionella. Scientists have been studying CSI and publishing many studies on the topic for over a decade since its introduction. This suggests that this method plays a key role in Legionella control for both hot and cold water (Chen et al. 2008, Lin et al. 2011).

Chlorine Dioxide

Another alternative systemic disinfection method is chlorine dioxide. This method could only maintain a sufficient residual concentration in the cold environment (Lin &Yu 2012). Although it is cheaper than CSI, it may be ineffective in hot water recirculating lines, because we may lose chlorine by evaporation.

Focal Methods

Present successful focal disinfection methods are long-lasting. One of them called point-to-use filtration is a typically useful preventive measure. Another one called superheat and flush was also successful at first. However, this was eventually abandoned because Legionella returned within one month (Stout & Yu, 2003). At the same time, it takes a long time to implement and complete with huge demands of labour (Stout & Yu, 2003). Researchers are still exploring short-term disinfection methods during outbreak situations.

How do these Methods compare?

Some control measures have been proven as effective methods for controlling Legionella. However, some others end up failing. For systemic disinfection methods, examples such as hyperchlorination and ultraviolet light have big problems in different ways. Hyperchlorination is highly expensive and it is one of the contributed factors for pipe corrosion (Lin et al. 2011). Furthermore, this method introduces carcinogenic compounds which may pose threat to the health of individuals. For focal disinfection methods, removal of deadlegs lacks scientific evidences. For the experiments of cleaning of distal outlets, the results show that Legionella could be eradicated only at the small-scaled outlets (Lin &Yu 2012). Therefore, copper and silver ionisation seems to me to be the best method to control pathogens in water.

Finally, although there are some ineffective Legionella control methods in water systems in the past, there are effective methods presently. Furthermore, it is plausible that new Legionella control methods will appear. This is due to research in measures against Legionella, as Legionnaires’ disease occurs and increasing media attention drives further research and surge of scientific publications.

References

- Chen Y. S., Lin Y. E., Liu Y. C., Huang W. K., Shih H. Y., Wann S. R., … Ke C. M. (2008). Efficacy of point-of-entry copper–silver ionisation system in eradicating Legionella pneumophila in a tropical tertiary care hospital: implications for hospitals contaminated with Legionella in both hot and cold water. Journal of Hospital Infection, 68(2):152-158.

- Collins S., Jorgensen F., Willis C., Walker J. (2015). Real-time PCR to supplement gold-standard culture-based detection of Legionella in environmental samples. Journal of Applied Microbiology 119(4): 1158–1169.

- Lapierre P., Nazarian E., Zhu Y.…et. al. (2017). Legionnaires’ Disease Outbreak Caused by Endemic Strain of Legionella pneumophila, New York, New York, USA, 2015. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23(11):1784-1791. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2311.170308

- Lin Y.E., Yu V.L. (2012). Legionnaires’ disease in nursing homes and long-term care facilitates: an emerging catastrophe. The Journal of Nursing Home Research.

- Lin Y.E., Stout J.E., Yu V.L. (2011). Controlling Legionella in hospital drinking water: an evidence-based review of disinfection methods. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 32:166-73.

- Stout J. E., Victor L. Y. (2003). Experiences of the first 16 hospitals using copper-silver ionization for Legionella control: implications for the evaluation of other disinfection modalities. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 24(8):563-568.

- Trnková K., Kotrbancová M., Špaleková M., Fulová M., Boledovičová J., Vesteg M. (2018) MALDI-TOF MS analysis as a useful tool for an identification of Legionella pneumophila, a facultatively pathogenic bacterium interacting with free-living amoebae: A case study from water supply system of hospitals in Bratislava (Slovakia). Experimental Parasitology 184, January 2018, Pages 97-102.

- Weiss D., Boyd C., Rakeman J. L., Greene S. K., Fitzhenry R., McProud T. … Fine A. D. (2017). A large community outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease associated with a cooling tower in New York City, 2015.

Blog post by ProEconomy Intern, Ruohan Pan (aka Laura) – MSc Student from King’s College London